Life in Brighton

At the outbreak of the Great War in July 1914, Samuel and Sarah Trask and their family were living in Brighton on the south coast of England. Their eldest child, Rose (Aunt Rose) aged 28, was working as the manageress of a refreshment bar; possibly Lyons at 14 North Street. Samuel and Sarah’s eldest son, Robert (Uncle Bob), was aged 26 and working as a porter in the Hotel Metropole, one of the two grand establishments on Brighton’s seafront. Samuel Ernest (Sam), my grandfather, was Samuel and Sarah’s third child and also worked at the Metropole: he was 24 years old and employed as a Wine and Spirit Cellar man. Their uncle, Sarah’s brother John Alsop, was also employed as a porter at the Metropole. John was 49 years old and had moved to Brighton after getting married in the mid-1890s: he may well have been partly responsible for the Trask family’s move to Brighton when Samuel retired from the police force in 1904 and have eased the path for his two nephews to gain employment at the Hotel Metropole.

Samuel’s fourth child, William Louis (Uncle Will), was 20 years old when war broke out and was working as a Window Dresser in a Gentleman’s Outfitters clothes shop.

At just turned 18 years old, Edwin (Uncle Dick), the youngest child in the family, was employed in the locomotive shed at Brighton railway station as a Machinist’s Lad. Working alongside him as Fitters were his two cousins John Charles Alsop and Edmund Alsop aged 23 and 22 respectively, who were both sons of Sarah’s brother John.

Bob and Will Enlist in the Grenadier Guards

When war was declared in the on the 28th of July, the 2nd Battalion of the Grenadier Guards quickly mobilised and deployed from Wellington Barracks to France via Southampton. It formed part of the British Expeditionary Force that was tasked to stop the German advance and prevent the fall of Paris. Being prominent in London society because of their ceremonial duties, the Grenadier Guards would undoubtedly have been seen and admired by the Trask family when they lived in Hackney. When the Grenadiers arrived at Le Havre on the 13th August, the Germans had already overrun most of Belgium and were marching southwest; they were met by the Grenadiers at Mons on the 23rd August 1914.

Probably inspired by news of the fighting in France, Robert Trask, Samuel Ernest and William Louis all visited the recruitment office in Brighton on 4th of September 1914 and volunteered to join the Grenadier Guards. Samuel Ernest was rejected at the medical examination due to having a “weak heart”, but both of his brothers were enlisted and reported for duty at Caterham Barracks, in Surrey, for basic Foot Guards training the very next day. Bob and Will were allocated regimental numbers of 18352 and 18353 respectively, and they both stated that they were living in their father’s house at 21 Trinity Street. Edwin did not enlist at that time because he had lost an eye in a workshop accident at Brighton railway station, so would have been medically ineligible.

Walter Spencer’s memories of training for the Grenadier Guards at Caterham Barracks from Sept to Dec 1914.

As Bob and Will had responded to the first call for volunteers, when they arrived at Caterham Barracks, they found that everything was in a state of chaos. New recruits had to sleep rough in the open air and it was several days before accommodation became available. They also had to wait until they had completed their basic training and relocated to London before uniforms and weapons were issued. Their training at Caterham lasted for 16 weeks and consisted largely of drill on the parade square and physical exercise designed to teach them to follow orders immediately and for them to learn basic military discipline.

Shortly after Christmas 1914, Bob and Will finished their training at Caterham and were moved by rail to Victoria Station in London, then marched to Chelsea Barracks. Chelsea Barracks was the home of the 4th (Reserve) Grenadier Guards Battalion whose task was to instil new recruits with the ethos of the Grenadier Guards and start to prepare them for front-line service.

Bob and Will would have handed in their civilian clothes when they arrived at Chelsea Barracks and been issued with khaki battle dress uniforms and other military kit. They were taught to use and look after their kit, but more importantly, they were issued with their own rifles and trained to fire them, and use them for bayonet combat, at various military firing ranges in and around London.

The 1st Battalion Grenadiers

While Bob and Will were undergoing their training and the 2nd Battalion of Grenadiers were fighting battles at Marne and Aisne, the 1st Battalion of Grenadiers was mobilised and moved from their barracks at Warley, in Essex. They assembled at Lyndhurst prior to deployment to Belgium, then crossed the Channel to land in Zeebrugge on the 7th of October 1914.

The 1st Battalion moved quickly towards Antwerp, but reached only as far as Ghent before being ordered to cover the retreat of the Belgian army. Heavily outgunned, Antwerp had capitulated on 8th October but the greater part of the Belgian troops had managed to escape. On the 11th of October, and just before the Germans reached Ghent, the 1st Battalion were ordered to fall back to Ypres and join the rest of the British Army to make a stand against the advancing Germans. Closely perused, the 1st Battalion reached Ypres early in the afternoon of the 14th of October, dug in, and met the enemy in what later became known as the First Battle of Ypres.

The fighting at Ypres during October 1914 was particularly fierce and by the time it subsided at the start of November the strength of the 1st Battalion had been reduced to only 25% of that which had landed in Zeebrugge less than a month before. Only five officers and 200 men remained; all the rest, probably over 600 men, had either been killed, wounded or were missing, so replacements were urgently required. By Christmas 1914, the fighting on the Western Front had stagnated and what remained of the 1st Battalion had repositioned to occupy trenches in the neighbourhood of Fleurbaix where it spent the winter.

Bob and Will join the 1st Battalion Grenadiers

Given the severe losses that the Grenadiers had suffered over the previous four months, Bob and Will were given only about four weeks of training at Chelsea before being transferred to the 1st Battalion of Grenadiers Guards and posted to join them on the front-line without any further delay.

They embarked from Southampton on the 9th of February 1915 and crossed the English Channel to arrive in France the next day. They immediately began training for life on the front-line at a base near to the coast. This included instruction on how to build and maintain trenches, how to live, work and fight in them, and how to use new weapons such as the Mills Bombs (hand-grenades).

Three weeks after they arrived in France, they moved forwards and joined the 1st Battalion battalion on the 2nd of March which, at that time, was manning the line of trenches in the region of Fleurbaix, west of Lille. Conditions in the trenches were poor with some sickness and occasional cases of influenza, and although problems with flooding had been partly solved, the insanitary conditions were also taking their toll. However, the Battalion was relieved by the Canadians on the next day and billeted in the Rue du Bois overnight. On the 4th of March, the battalion marched to Neuf Berquin and on the following day, to Estaires where they spent five days to rest, recover and prepare for their next battle which was already being planned.

Bob Repatriated

At some point on the 8th of March, Bob reported to the medics suffering from Piles; he had probably been affected whilst in the trenches, and marching may have exacerbated the problem so he took the opportunity to report sick whilst resting in Estaires. His condition was obviously bad enough for him to be withdrawn from the front line, evacuated back to England and admitted to the Military Hospital Hampstead for treatment.

Bob spent 20 days in hospital and had surgery to treat his piles. Sadly though, this wasn’t successful and he became incontinent. So four months later, on the 23rd of July, he was admitted to the King George hospital in London for further surgery to cure the problem. It took until the 4th of October for him to become well enough to be released and return to his battalion.

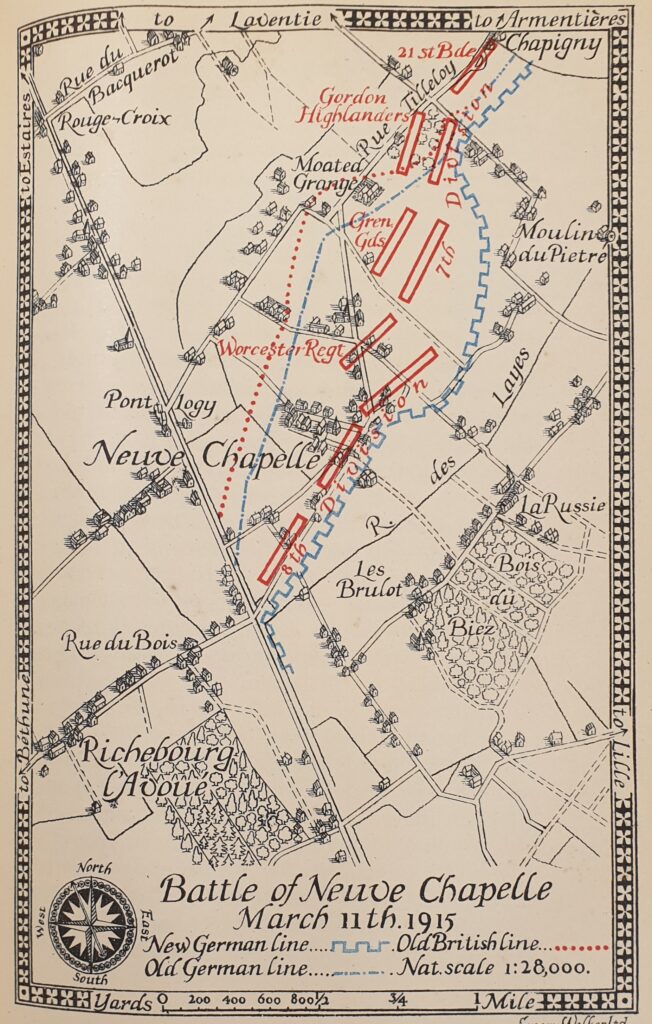

Will – The Battle of Neuve Chapelle – March 1915

After being parted from his older brother, Will remained with the 1st Battalion and prepared for battle. After heavy French losses sustained in early 1915, French and British commanders had agreed that the next large attack should be undertaken by British forces on the German front line near the village of Neuve Chapelle. The 1st Battalion of Grenadiers had been chosen to be part of the reserve brigade supporting that attack which was due to begin at 7:30am on the 10th of March 1915, just eight days after Will had arrived on the front-line.

As the battle began, poor communications, atrocious conditions and confusing orders resulted in initial gains being thrown away. Delays in calling up the reserve forces meant that the 1st Battalion of Grenadiers did not begin to move up to the old British front-line of trenches until 4am on the morning of the 11th.

At 7am that morning, the Battalion started to advance towards their objectives that were located beyond old German trenches that had been captured the day before. However, the rapidly changing situation, coupled with a landscape that had become unrecognisable due to shelling, caused confusion and many men were killed or wounded by enemy fire coming from pockets of enemy forces that had withstood the initial British assault and advance. As darkness fell, the 1st Battalion withdrew to some reserve trenches having taken heavy casualties. Exhausted, hungry and wet through, they spent a difficult night under heavy shell-fire.

During the afternoon of the 12th, the 1st Battalion was ordered to support the Scots Guards and Border Regiment who were to make an attack. Although the orders seemed straightforward, platoon commanders had difficulty interpreting them against a landscape that had been completely changed by days of shellfire. Many of the battalion quickly became pinned down by enemy machine-gun fire and others got lost in the labyrinth of trenches and shell-holes, but eventually the right half of the battalion managed to get into position to give support. Seeing an opportunity to capture another bit of German trench, a small party of Grenadiers attacked with bombs and almost single-handedly captured over one hundred enemy troops; for this action, two men were each awarded the Victoria Cross. As the battalion withdrew to their original line for the night, they counted that only seven of their officers remained from the original twenty-two that started the battle.

Early on the morning of the 13th, the 1st Battalion were ordered to relieve the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the front-line and then to make an attack. The battalion started moving forward at 3:30am in an effort to travel the 1000 yards to reach and relieve the Fusiliers before daybreak, but again, progress was painfully slow due to the conditions and obstacles. They finally reached the Fusiliers just as it was getting light and to their horror, realised that the Fusiliers filled what trenches there were and that there was not enough room for the Grenadiers to take cover; the Fusiliers could not now retire and vacate the trenches as planned because they would have been easy targets in the daylight.

Two men were observed to get up and walk about, and were shouted at and told to lie down. All they did was smile inanely, and very soon, of course, they were shot by the enemy. They had gone clean off their heads.

The Grenadier Guards 1914 – 1918; Ponsonby

The Grenadiers therefore tried desperately to dig-in, but their efforts amounted to little more than shallow scratchings. Soon after daybreak the enemy fire became intense and the whole ground was ploughed up with shells and furrowed with machine-gun bullets; the noise was so intense that orders could not be passed and communications became all but impossible. With no way to escape, and an attack out of the question, the Grenadiers were forced to endure the shelling and gun-fire for hours until darkness made escape possible.

It was probably during this engagement that Will received a gun-shot wound to his head; his service records report that he was wounded sometime that day. Later reports of the action on the 13th of March highly praised the bravery of the battalion stretcher-bearers who succoured the wounded oblivious of bullets flying and shells bursting around them; they probably saved Will’s life. The remains of the battalion managed to withdraw after dark, but a head-count revealed that about 75% of their officers and 50% of their men had been killed or injured over the previous three days.

Probably unconscientious, Will was taken to the field hospital and transported back to England three days later. He was admitted to Trinity Hall Hospital, Sittingbourne in Kent, on the 17th of March and found to have a bullet wound to the right side of his head, just above his ear. He had been very lucky, his skin had been grazed and he had some bruising, but no major injury that delayed his recovery; he was discharged after only eight days in hospital and transferred to the 4th (Reserve) Battalion.

Will transfers to the 4th Battalion – July 1915

During July 1915, the King decided to raise a new battalion of Grenadier Guards. Despite the hideous losses on the front-line, the 4th (Reserve) Battalion had swollen in size because of the rapid arrival of newly trained recruits, so a new 5th (Reserve) Battalion was created and the 4th Battalion became fully operational. Having recovered from his wound, Will was transferred to the new 4th Battalion of the Grenadiers on the 19th of July, just a few days after its formation. Since he had already spent several days in combat, Will was probably viewed as one of the more experienced Guardsmen amongst the new recruits.

Walter Spencer’s memories of travelling to the front line with the 4th Battalion of Grenadier Guards in August 1915.

The day after Will’s transfer, the 4th Battalion moved to Bovingdon Camp in Dorset to prepare for deployment to the front-line. On the 15th of August, they embarked at Southampton on the “RMS Empress Queen”, a steel paddle steamer that had been chartered from the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company, and crossed the Channel to Le Havre. They then proceeded by train to St Omer, then marched to the village of Blendecques, about 2km to the south, where they remained until late September and prepared for the first big coordinated attack on the enemy lines.

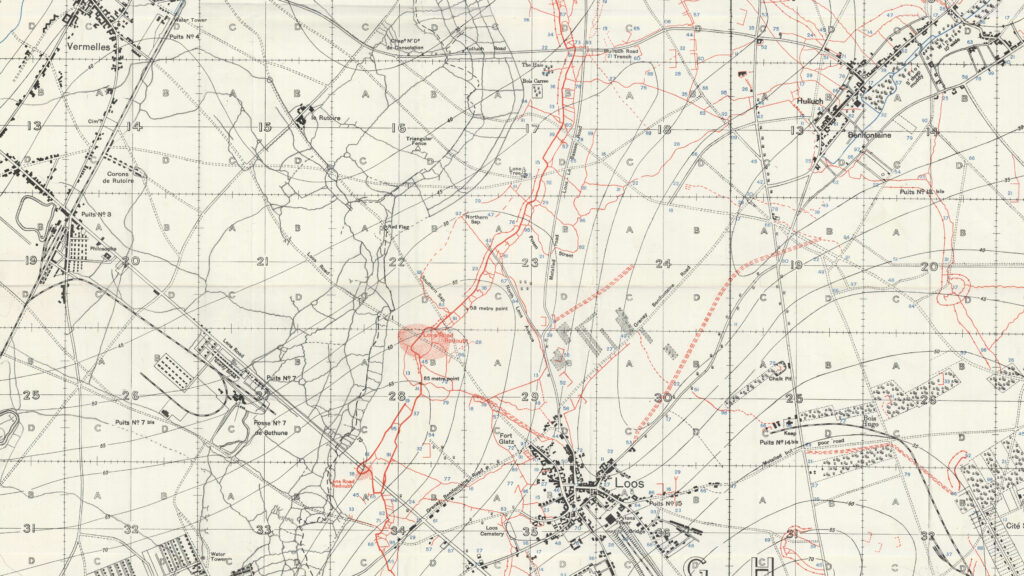

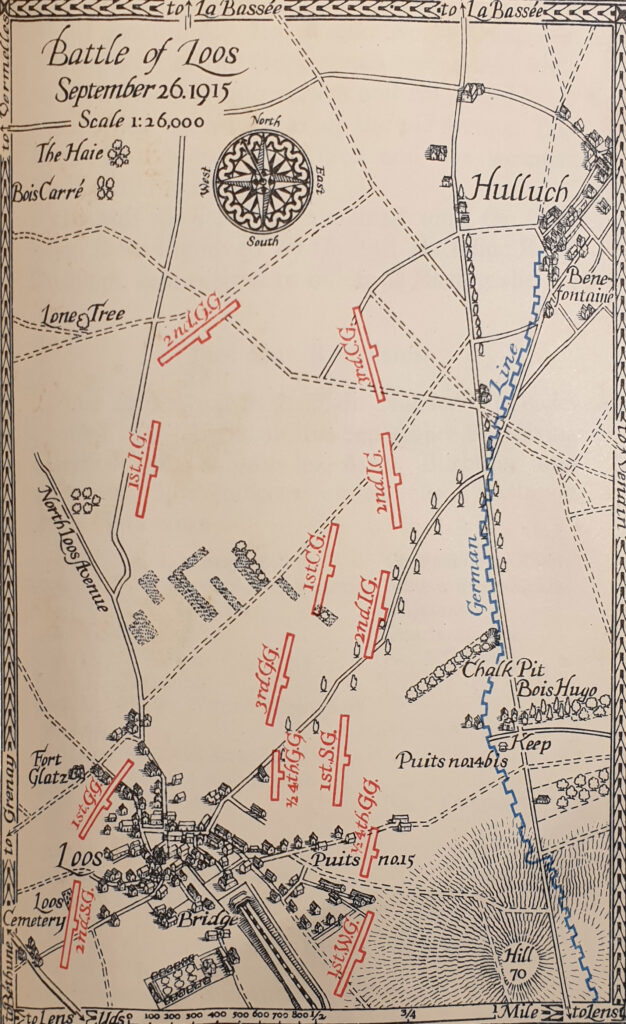

Will – Battle of Loos – September 1915

The aim of the planned offensive was for British forces to break through the enemy lines between Lens and the La Bassée canal while French troops would force their way through the lines south of Lens. The “Big Push”, as it became known, began at 6:30am on Saturday the 25th of September after four days of continuous artillery bombardment that included the use of gas shells. Being part of the 3rd Guards Brigade, the 4th Battalion of Grenadiers were initially held in reserve and arrived at Haillicourt, more than 10 miles from the fighting, during the morning of Sunday the 26th.

Walter Spencer’s memories of the Battle of Loos – Sept 1915.

Will and his fellow members of the 4th Battalion were crowded into billets for a short time during which they could clearly hear the violent bombardment of the French attack at Souchez. In the afternoon of the 26th, the battalion marched closer to the front line and arrived at the ruined village of Vermelles, to the north-west of Loos, where it rested. Early on the Monday morning, they were given orders to advance through Loos and mount an attack on Hill 70 (so called because the summit of the hill was defined by the 70ft contour line) which had been reinforced by the enemy.

At 2:30am in the morning of Monday the 27th of September, the 4th Battalion marched, in fours, down the main road from Vermelles to Loos. As they approached the old German front line at the top of a ridge half a mile before Loos, they found the remains of hundreds of British troops that had been killed during the initial assault two days previously. Many were still hanging on barbed wire entanglements where they had been trapped and shot, but many others had been mown down by machine gun fire. Once they had passed the German trenches, the Grenadiers advanced in artillery formation downhill towards Loos; but now being in full view of the enemy, they were under constant machine gun fire from their right and heavily shelled by the Germans who had retreated into Loos and beyond.

Nearing Loos, the Grenadiers were ordered to double down the slope and enter an old German communications trench, just north of Fort Glatz, that ran through some ruined houses on the northern edge of Loos. As they were doing so, the tail end of the battalion were intercepted by General Heyworth, their brigade commander, and ordered to follow him through the centre of Loos. The German artillery was now being directed at Loos and contained a large number of gas shells as well and conventional warheads, so progress through the town was slow and difficult. Moreover, the battalion had now been split, with the largest part not being in communication with commanders and positioned to the left, and cut off from, the smaller element. It is not known in which section Will was positioned at that time.

The part of the battalion that advanced through the centre of the town encountered many snipers and also suffered casualties from chlorine gas shells. However, they finally established a position on the eastern edge of the town facing Hill 70.

Meanwhile, the larger section of the battalion that was positioned further to the north, paused in the hope of receiving orders for the attack on Hill 70. Unfortunately, contact could not be established, so rather than doing nothing, their commanding officer decided to join in an attack on a coal-mine head, Puits No. 14 Bis, situated on the northern side of Hill 70. They advanced under heavy machine-gun fire but eventually became completely isolated. Realising that no further advance was possible, they crawled back and dug in on the Hulluch to Loos road.

Shortly after that attack, the smaller part of the battalion joined with some Welsh Guards to make a head-on attack on Hill 70. They initially made good progress, but on reaching the crest of the hill were cut down by murderous machine-gun fire. They finally dug in below the crest of the hill as darkness began to fall. All of the Grenadier’s officers that took part in that attack were either killed or badly wounded.

Overnight, the 4th Battalion gradually reformed on the Hulluch to Loos road where they remained for the rest of the next day, the 28th of September. However, there were still fifty men pinned down on Hill 70 and it was not until the following night that they were rescued by advancing Scots Guards.

When the battalion finally marched back to Vermelles on the 29th of September, they discovered that over half of their officers and a third of their other ranks (342 men) had been killed, wounded or were missing. Once again, Will had been extremely lucky to survive without injury.

After their heavy losses at Loos, the 4th Battalion were billeted at La Bourse until the 3rd of October when it was ordered to occupy the trenches on the left of the Hulluch to Vermelles road. The system of trenches in that position were highly complicated and the battalion had to assist with extensive works on them. There was always a certain amount of shelling and they were not safe even when resting in Vermelles during their two-days-off in the trench manning pattern; at least one officer was killed by a high-explosive shell whilst going round the billets.

At the end of October 1915, the 4th Battalion retired to Allouagne for three weeks recovery. Then on the 14th of November Will and the battalion marched via Estaires, La Bassee road and Pont du Hem to occupy the trenches from Chapigny to Winchester road. They remained there for the rest of the year and apart from a highly successful raid on enemy trenches on the 12th of December, trench life became routine.

Bob and Sam Marry in Brighton – November 1915

By October 1915, Bob had recuperated from his second operation and was given orders to return to the front line. Granted a short period of leave before deployment, he obviously took the opportunity to return home to Brighton. It was there, on the 6th of November, that Bob married Mary Jane Lamborn. He had probably known Mary for some years because she had been living in and working as a chambermaid at the Hotel Metropole during the night of the 1911 census. Eleven days after Bob and Mary were married, on the 17th of November, his younger brother, Sam, married Miriam Florence Anderson at the same registry office. Less than a fortnight afterwards, on the 29th of November, Robert travelled to Southampton to return to the Western Front; he left his new wife living with Sam and Miriam (my grandmother was known as Flo) in what was the Trask family home 21 Trinity Street, Brighton.

Recent Comments